Ukiyo-e (浮世絵) prints and paintings date back to the 17th century, and lasted up until the 19th century. Edo (present-day Tokyo), served as a hub for artists to create and sell their art, and the style and subjects of these pieces of art ranged and varied dramatically.

The word “ukiyo-e” means “pictures of the floating world” (broken down: 浮 – floating, 世 – world, 絵 – picture(s)), and refers to the popular style of woodblock printing prominent in East Asia.

Takiyasha the Witch and the Skeleton Spectre by Utagawa Kuniyoshi; Japanese Title: 相馬の古内裏 妖怪がしゃどくろと戦う大宅太郎光圀

This first piece by Utagawa Kuniyoshi (歌川 国芳) (3, 6) depicts Takiyasha, a princess from the 10th century, summoning a skeleton spectre to scare away Ōya no Mitsukuni, a Minamoto samurai. You can see Princess Takiyasha reading off a scroll to summon the large skeleton, and Ōya no Mitsukuni staring into the face of the skeleton with his companion ducking away from it. Ōya no Mitsukuni is known in the story/mythical lore that this picture is based on as an hero that was able to defeat the skeleton spectre and Princess Takiyasha.

I chose this piece to showcase first because I had never seen something like this depicted in ukiyo-e before. Whenever I have heard or learned about the subject in school, I was always shown the weird-drawn people or landscapes that feature Mount Fuji or the famous Giant Wave print. It surprised me to see such a thing as this, I and knew I had to include it in my exhibit. Through this picture, was able to learn something new about Japanese lore that I had not known before.

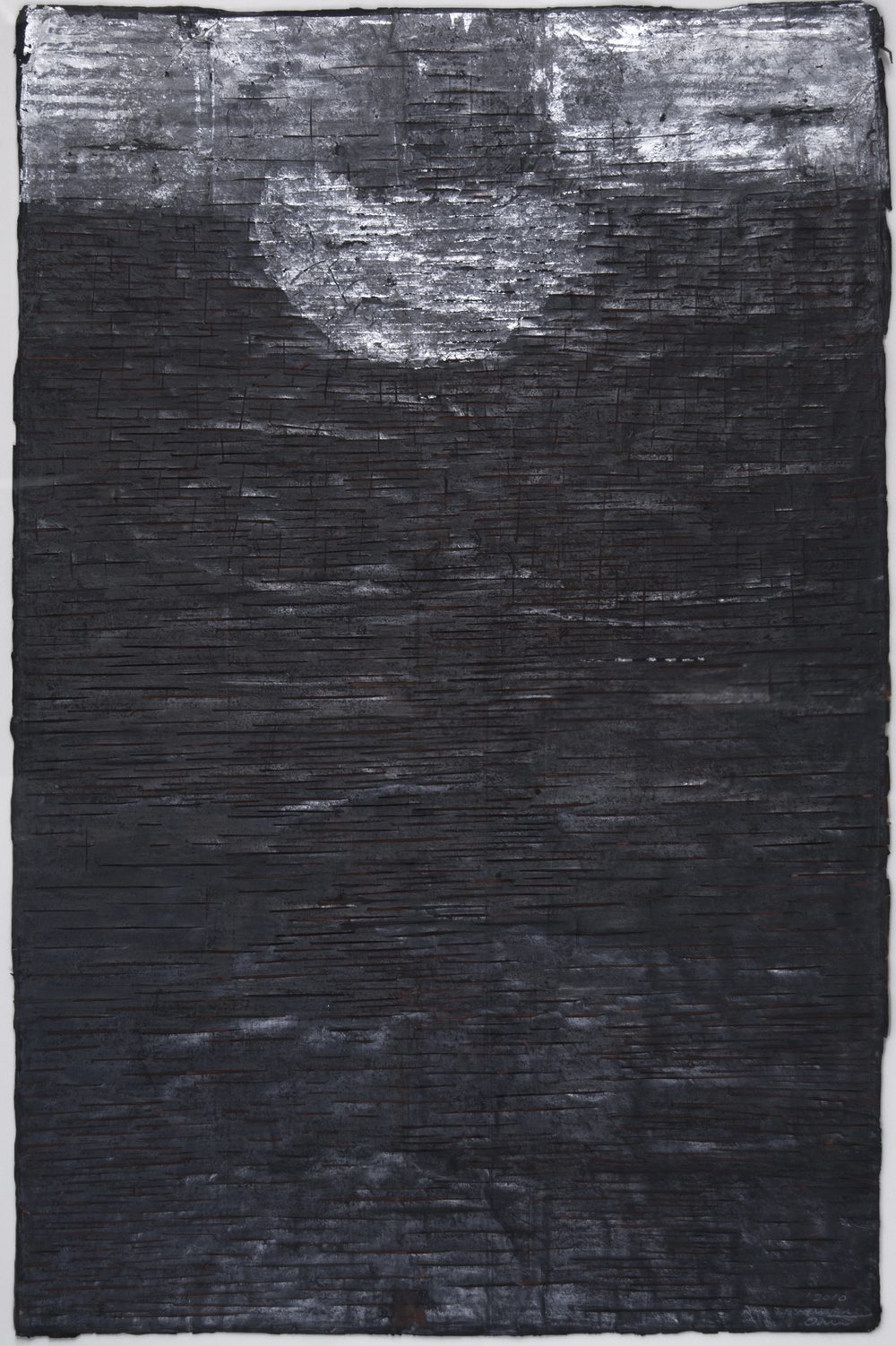

This piece, also by Utagawa (6), shows ukiyo-e in the vertical format. Not much was written about this piece as far as history or context, but I chose this pieces because of the colours and subject matter.

The hawk in the work was painted to be quite realistic. The details and work put into this piece make it so that the hawk has its individual feathers defined. The face is intense, and I think the red on either side of its head makes it stand out even more. The leaves and foliage on the tree also have a lot of detail and thought, and it feels as though the hawk will fly off the branch any moment, and the some of the leaves will fall off and land on my desk. Having it painted in a vertical fashion really complimented the composition.

This piece is six vertical pieces put together to create one big picture/scene. “In the foreground, samurai, monks, and ladies enjoy a drinking party at a famous spot for viewing the autumn leaves on the banks of the Kiyotaki River in the Takao area of the northwest outskirts of Kyoto. In the left background we see snow-blanketed Mount Atago, and in the right background are the buildings of the Jingoji Temple” (4). Painted by non-monk Kanō Hideyori (狩野秀頼), this was one of the original works from what started from “Chinese paintings,” works from the Song Dynasty that depicted Chinese landscapes. When Japanese artist began using this style, they were usually exact copies of the original. The monks later began to create more original works and creating and establishing their own styles. Kanō is known for his lively and bright colours.

This piece reminds of me of the art from the Romantic era, where Western artists painted scenes from life. Often people who were in parks sitting in the grass having picnics and enjoying some the good weather. This piece differs in that it looks like a map, showing general locations in a not-to-scale fashion. I really like the colours and how they seem to grow out of the brown surroundings.

Oniji Ōtani III (aka. Nakazō Nakamura II) as Edobee in the May 1794 production of Koi Nyōbo Somewake Tazuna at Edo Kawarasaki-za theater

Here in this piece, “Otani Oniji II is captured here in the role of Yakko Edobe. A yakko is a manservant often used by samurai to perform violent deeds” (5). Otani Oniji was an actor in the theatrical art form of kabuki (歌舞伎). Sharaku Toshusai, the artist, was very well known for his dramatic depictions and vivid colours in his art.

The thing that stands out to me about this piece is the detail in the hair. It’s the first thing my eyes jump to when I look at it. Then I look at the face. I think for most people, they would notice the face first because it’s so wacky looking and silly. It makes me wonder how close the resemblance is to the real actor, and if he often look silly like this.

For more ukiyo-e paintings, there is an extensive gallery here. Enjoy!

1. “Artists by Movement: Ukiyo-e – Images from the Floating World.” Artcyclopedia. Web. 25 Apr. 2015. <http://www.artcyclopedia.com/history/ukiyo-e.html>.

2. Department of Asian Art. “Woodblock Prints in the Ukiyo-e Style”. In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/ukiy/hd_ukiy.htm (October 2003)

3. “A Brief Biography of Utagawa Kuniyoshi.” Kuniyoshi Project. Web. 25 Apr. 2015. <http://www.kuniyoshiproject.com/Kuniyoshi Biography.htm>.

4. “Overview of Painting of The Muromachi Period (1333-1568).” Web Japan. Web. 25 Apr. 2015. <http://web-japan.org/museum/painthist/phmuroj/phmuroj.html>.

5. “Toshusai Sharaku: Otani Oniji II” (JP2822) In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History . New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/works-of-art/JP2822. (October 2006)

6. “Utagawa Kuniyoshi.” Ukiyo-e. Web. 25 Apr. 2015. <http://ukiyo-e.org/artist/utagawa-kuniyoshi>.